Ash & Smoke

L.A. teacher deals with smoke damage after Marshall Fire

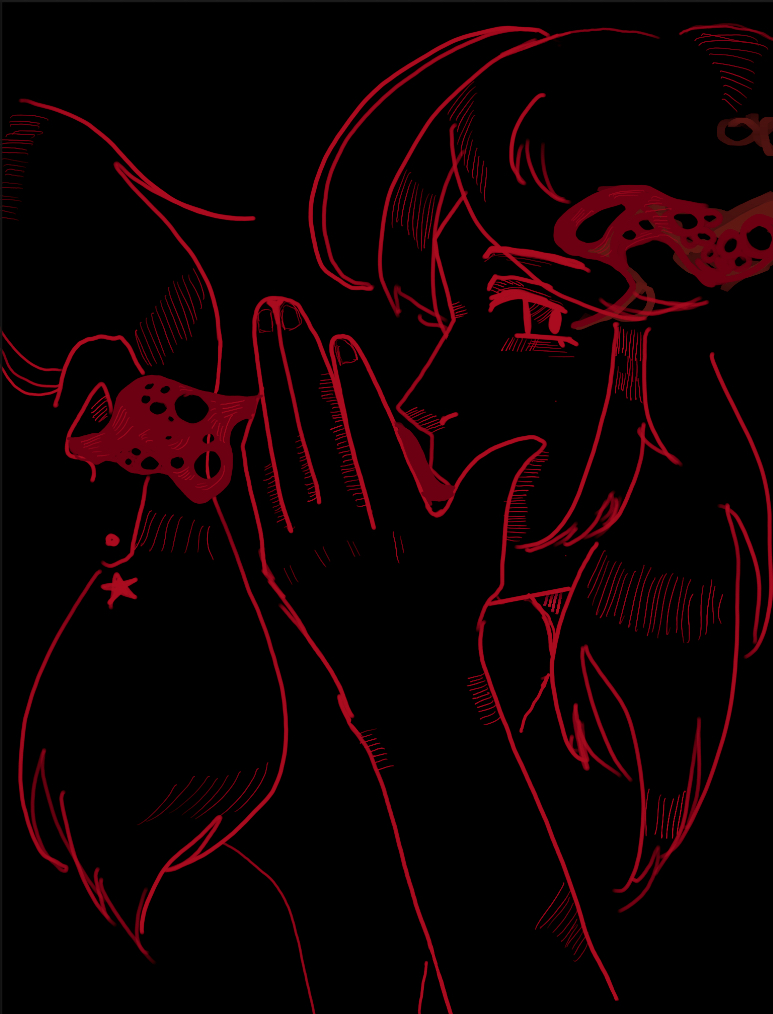

The air inside language arts teacher Taryn Cawlfield’s house was heavy and thick with cold smoke last winter, her shoes leaving footprints in the thin layer of black ash on the floor. A Christmas tree stood solitary in her living room, ornaments dusted in soot.

Cawlfield was one of hundreds Louisville and Superior residents who experienced serious smoke damage from the Marshall Fire on Dec. 30, 2021. Closely surrounded by destroyed homes, her house was vulnerable to the toxic smoke produced by the fire.

“When we came home, it was covered in black ash everywhere,” Cawlfield said. “We had N95 Masks on because you could smell the toxins and metals.”

Cawlfield and her family were displaced for weeks while her house underwent cleaning and restoration.

“We lived in a hotel for a month and a half,” Cawlfield said. “It was hard because we just had one little room.”

Unlike regular grass fires, the smoke from the Marshall Fire contained dangerous chemicals found in plastics, textiles, electronics, and other household items because so many homes burned. Tiny smoke particles can enter the lungs and lead to a number of life-threatening health problems, including heart conditions and cancer.

In the wake of so much destruction, cleaners and contractors were in short supply.

“I luckily found these guys just from being on the internet for hours,” Cawlfield said. “They were local and independent workers, and they were really good at proving to insurance that we needed all the insulation in our crawlspace changed out and sealed.”

Insurance was one of the biggest challenges for victims of smoke damage. While a house burned to the ground is undeniably unsalvageable, it’s harder to get insurance to pay for household items invisibly contaminated with toxins.

“We were very grateful for our house, but we were dealing with insurance every day, and they didn’t want to cover any of the issues,” Cawlfield said.

Some things weren’t salvageable. In addition to all of her linens, pillows, and bedding, Cawlfield had to replace her couch and many of her clothes. Insurance didn’t help cover all of these expenses.

Besides the surface-level impacts of smoke damage, Cawlfield also described how the pain she felt to enter the new year with her own house still standing when many of her friends, colleagues, and students had lost theirs.

“I had the guilt of ‘I shouldn’t feel bad because I didn’t lose my house.’ It’s that survivor’s guilt,” she said. “I was telling my students that it’s okay to be sad even if you didn’t lose your house. And I was trying to tell myself the same thing.”

Cawlfield knows the fire impacted people in many different ways, and wants her students to recognize that every experience is personal and just as valid as anyone else’s.

“When grief is a very broad experience, people will tend to put grief on some kind of hierarchy,” Cawlfield said. “Like ‘I lost more,’ or, ‘I suffered more,’ and I think that’s very problematic.”

Looking forward, she hopes to fight for the establishment of better fire prevention measures in Louisville.

“It’s something I can see, when I’m in a better headspace, that I will confront and try to change,” Cawlfield said. “That’s how I know we’re still in a fragile state, that I’m not even ready to be pushy about it.”

Now, a full year since the Marshall Fire, she still feels the long-term psychological and emotional impacts of a disaster shared by the community.

“Hopefully, this experience has taught people to listen to other people’s pain,” Cawfield said.