A false threat | As real as it gets

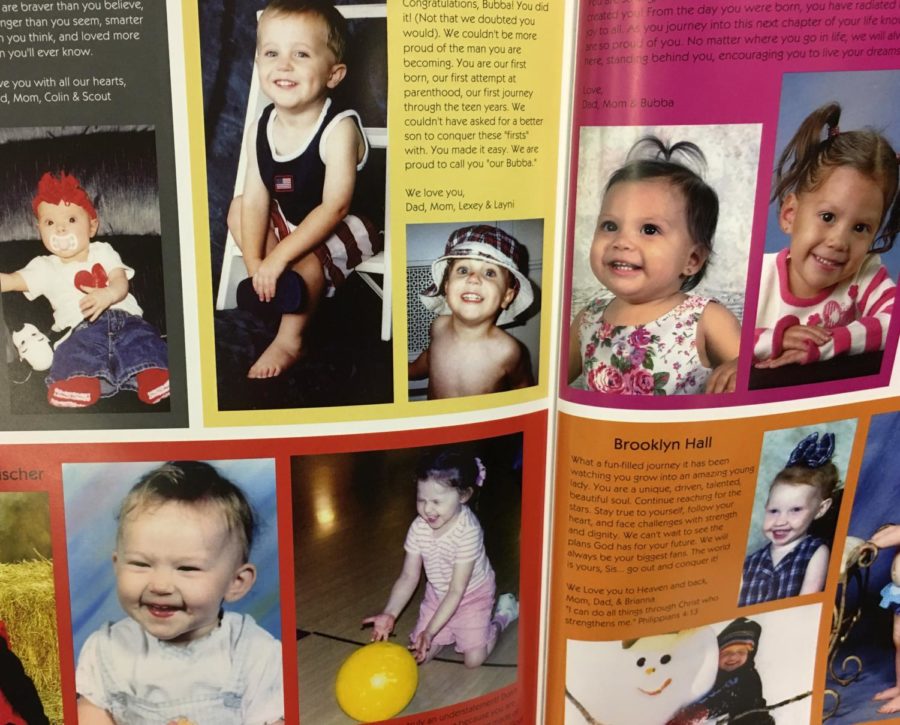

Boulder High School swatting traumatizes community

John Herrick from Boulder Reporting Lab

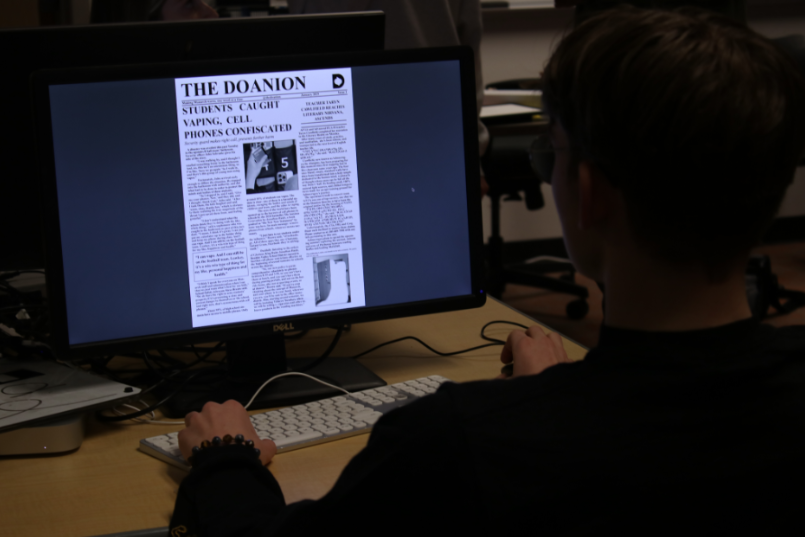

EMT vehicles and police stand outside Boulder High School on Feb. 22. Police were called to the school with information that a person was entering the school with a gun. The call was a hoax called “swatting.”

Steam rose from Boulder High School Assistant Principal Scott Cawlfield’s coffee mug as he leaned back in his office chair, peering out his office window into the snowy Wednesday morning.

As Arapahoe Avenue slowly filled with students on February 22, a police cruiser suddenly veered into the campus parking lot. Dozens of officers emerged from their cars and stormed towards the entrance.

“I ran to the front office door to greet them, and it was at that time that they let us know that they had gotten a call,” Cawlfield said. “The caller had said they were at Boulder High School with a gun, and they were going to go in and cause harm.”

In under three minutes, the school was surrounded and infiltrated by 50 police officers.

“We immediately went into lockdown,” he said.

At 8:56, Cawlfield began coordinating with officers and the district security team about how to follow protocols for the emergency.

“They needed to know the building, so I handed out maps so they knew where to go and mark off what was searched,” he said.

At the same time, science teacher Johnathon Evans led a book study with five other teachers in his classroom. After hearing the lockdown announcement echo through the school speakers, Evans barricaded his classroom doors.

“We were texting our wives and our children and developing a plan,” Evans said. “I was ready to grab a desk and throw it while the other folks were going to charge. I was hiding in a room ready to risk my life if it came to it.”

For over an hour, the six teachers in room 2607 sat in complete silence, until a knock sounded at the door.

“When they knock on the door and say, ‘Hey, we’re the police,’ we’re trained not to believe them,” Evans said. “The whole door was barricaded, so we had to peek through a part of the window to verify they were definitely police.”

Six officers from the Boulder SWAT escorted the teachers toward the main office, equipped with rifles and body armor.

“They had us in the middle of their circle, and we went through the main halls that they had deemed safe,” he said. “They relocated us to the main office hall, the designated safe zone.”

At 10:30, Macky Auditorium at the University of Colorado was set up as a reunification site for staff and students.

“We got students and any of their parents out on the first bus, and then teachers took a second bus,” he said. “We were at Macky Auditorium for what felt like forever.”

What felt like forever to Evans turned out to be only half an hour. When the lockdown was lifted at 11 A.M., the community found out that there had been no shooter, or any real threat toward the school.

Boulder High School had just been swatted.

“It’s frustrating that somebody is preying upon a school, which is typically a safer environment,“ Cawlfield said. “They’re targeting us just for their own pleasure.”

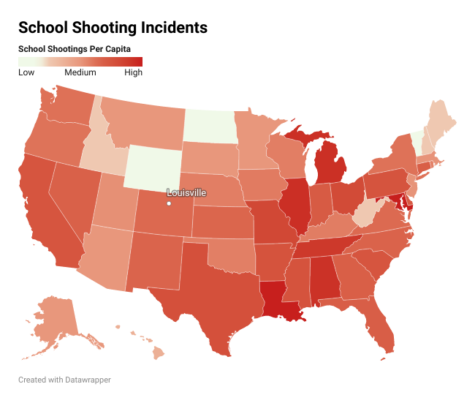

On Feb. 22, Boulder High School was one of 19 schools in 15 Colorado school districts to receive similar swatting calls.

“These threats carry so much power due to the potential of it being real,” Evans said. “How do we do a better job of filtering these calls, especially as criminals and terrorists become more savvy?”

With the rise of swatting incidents across the country, victims experience an emotional toll, causing anger and frustration.

“My emotions felt invalidated,” he said. “I discussed with my coworkers that it is okay to be traumatized. Even though we learned what we experienced wasn’t real at the end, it felt real.”

While Monarch wasn’t affected that day, science teacher Courtney Van der Linden has concerns about swatting in the community.

“It’s definitely in the back of your mind, and it’s always something to think about,” Van der Linden said. “The reason we do drills and practice is so that our brains are ready in that case.”

With practice, panic turns into procedure, so school staff members and police officers know how to handle the situation.

With the recent history of shootings fresh in the minds of the community, the bravery of the Boulder Police Department deeply impressed Van der Linden.

“The swatting incident at Boulder High was very unfortunate and traumatic, but it was also great how quickly the officers responded,” she said.

Evans agreed.

“It was literally minutes,” he said. “Being two years removed from the King Soopers shooting where one of their officers died, they don’t wait, they just go protect people.”

While the Boulder Police Department acted quickly, the impact of these swatting events will last within the community.

“It’s the trauma essentially, that people went through that day, not knowing if it was real or not,” Cawlfield said. “For those of us who were there, it was as real as it gets.”