Entertainment in the age of social distancing

How the TV and Film industries are being affected by the COVID-19 pandemic

The light rigging on set at an ad for Chili’s from 2019

Raise your hand if you’ve caught yourself binge watching way too much TV or found yourself deep down the rabbit hole of Cinema during quarantine.

Anybody? Everybody?

Yeah.

In 2015, Amazon very accurately coined the term “The Showhole.” This refers to the feeling of post-finale depression experienced by anyone who’s finally polished off every episode of “the best show ever.” Now imagine that feeling, but instead of reaching the end of your favorite series, you’ve reached the end of your favorite genre. In 2019, this would’ve been an inconceivable premise. But in 2020, given the circumstances facing the planet, it could become very real.

The 2019 smash-hit show Euphoria (TV-MA) took 465 people working behind the scenes and eight months to produce, not including the expansive case of leading actors and extras.

A 60-second ad for Chilis created in 2019 took 16 hours, 28 crew members, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in equipment and salaries, just so it could be shot. That’s ignoring the time invested by another twenty-or-so people to come up with the concept and plan the whole thing, who traditionally work side by side in a small office trying to make the whole thing happen.

Here’s the point: it takes time, money, coordination, and most importantly, a lot of people in generally very close quarters to make the content we watch on our screens. It’s an entire industry. And given the Social Distancing required by the COVID-19 pandemic, the industry’s current way of doing things is an impossibility.

Tim McOsker, VP of Production and Development at Citizen Pictures, the mind and the company behind productions such as Food Network’s Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives, Comcast’s X1 Platform ad campaign, and a number of other prevalent waves in Network TV knows this as well as anyone. “Production for television is usually four to six months out from its release date,” he said. “What you’re going to really see is [social distancing] affecting any kind of programming that you’re looking at airing in October through December of next year and beyond.”

But what does that really entail? Essentially, it means that most of the TV that would’ve been shot and produced at the time of writing this article is what would be aired as far out as the fourth quarter in 2021.

“Traditionally, people are building out their cable network calendar,” McOsker said. “So what you’re seeing now is a lot of production that can’t be done, and that leaves holes in the production schedule that need to be filled somehow.” Filling those holes is where the challenges come in.

If a production can’t have more than ten people in a room, assuming its team is even willing to break quarantine altogether, then how are they going to achieve the task of crafting the beautiful images and compelling stories that Americans come to expect 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year?

McOsker sees the standard producers of the media are grasping at straws right now. “People who do YouTube or TikTok and make a living doing what they do are way ahead of the curve. All these network TV dinosaurs like us are like, oh, maybe we could make a TV show by just doing Zoom footage, or maybe we’ll do clip shows of like, greatest hits,” he said.

McOsker is altering the way shows like Diners, Drive-ins and Dives on the fly. “Guy Fieri’s going to cook in his kitchen, and he’s going to be on Zoom, and he’s going to be talking to chefs around the country who are also on Zoom,” he said. “So whether or not that’s going to be a great program to watch, who knows. But I think it’ll be fun.”

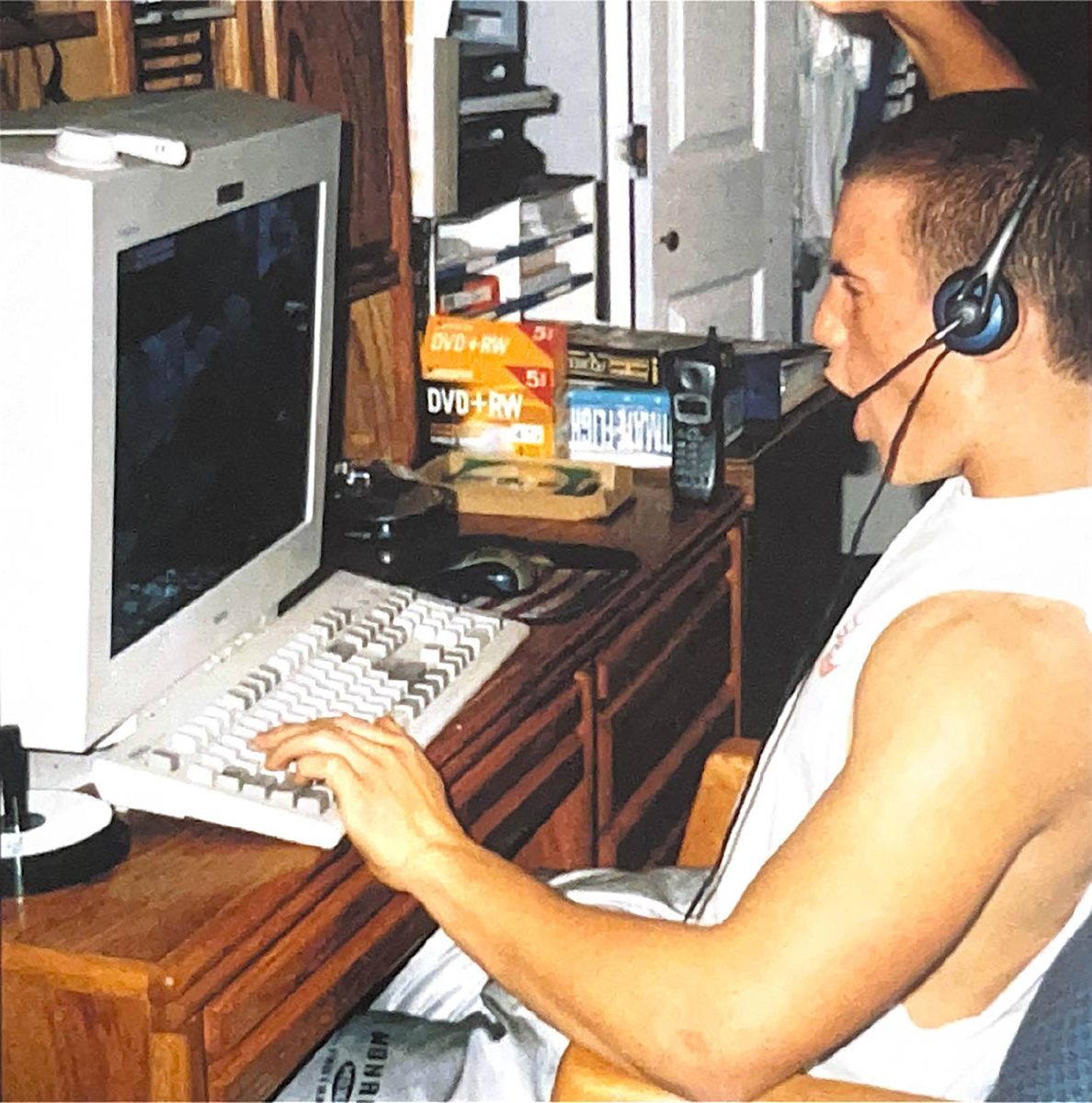

The setup for that shoot consisted of several GoPros around the kitchen, two MacBooks, one running a conference with a stripped-down production staff, and the other hosting the faces of Fieri’s guests, with his son Hunter behind all of the cameras acting as the producer for the shoot.

McOsker and his peers in network TV aren’t the only people in the industry feeling the heat. Smaller productions, such as short films, advertisements for small businesses and music videos for local musicians are also having to cope with the side effects of Social Distancing.

The story of Peter Garland, a one-man-band freelancer and the owner of Brave Knight Media based in Thornton, a live camera operator for venues like Red Rocks, and a member of the board of directors and teacher at Reel Kids in Superior, is one of a man whose livelihood in film has been as directly affected by the pandemic as possible.

“When I started Brave Knight in 2018, I left a job as a software engineer that paid me a lot of money, and I was basically starting over from scratch, so our finances two years ago dramatically dropped,” Garland said. “Leaving February of this year heading into March, I had about $4,000 worth of jobs lined up. That was going to be my biggest month of new business so far, but we were sort of seeing the writing on the wall. And on Friday the 13th, all of the things that I had scheduled canceled on me.”

Garland has a wife and two kids, so it’s understandable that as a man trying to strike out and follow his passion while also providing for his family, he was going through hard times even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Leading up to all the shutdowns, I very much had been watching the news during this whole January, February, March period of the COVID-19 virus,” he said. “So I would watch, and really my main focus was as a human being with a family. In many respects, I’ve been operating in this mode for two years now. So I’m like, ‘Okay, there’s no money coming in this month. What do I do, right?’”

This new world is forcing Garland to pivot and take his skills into new areas. “There’ll be some real estate, virtual tours or something. I haven’t looked into that, but I could see one photographer/videographer going to an empty house, where there’s no chance of translating any kind of virus or whatnot,” he said.

Garland also believes firmly in the power of education. “I teach editing, and I teach some video production to like a bunch of middle school kids or older at Reel Kids,” he said. “Most of those classes are in-person and were cancelled, but I still have a virtual Zoom class with some of them once a week. From that I get a very small amount of income, it’s only like an hour and a half a week.”

In addition to being a mentor and a teacher, he’s also taking this time to educate himself. “I’m going to get on YouTube and learn this or ‘m going to get over here and learn that. I’ve started trying to pick up some skills completely out of my wheelhouse, and that’s really cool. I have always been a lifelong learner.”

Another grassroots project is the indie short film Five Minutes, which is being spearheaded by a group of local high school students, leading a mix of their peers, college students, and adults from around the community.

17-year-old Julia Jacobson is a writer and co-director for the project.: “Right now we’re perpetually locked in pre production,” she said.” It’s definitely been a bit of a challenge for everyone to work remotely, given the fact that not everyone in the team has a great internet connection. Some people don’t even have laptops. So far, that’s affected us more in rehearsal and meetings with the entire cast than it has on the production side of things, just because that’s a smaller group of people and most of us on that end already have pretty established setups for video conferencing.”

Jacobson said this project is ambitious in scope. “We really want to set a precedent for what low-end production could really be. With enough careful planning and forethought – and I’m talking about a level of microscopic detail down to exactly what shade of lipstick our leading actresses will wear, as a number – I believe that we can craft something that looks like Netflix or HBO paid a lot of money for it. Something truly magical.”

In some ways, Five Minutes has actually benefited from the COVID-19 situation. “I don’t think we would’ve been as driven and motivated as we are now to move the project forward if we weren’t all stuck at home with little to do,” Jacobson said. “Most of us–almost all of us–come from a background working entirely on theatre. Our entire cast is made of stage actors and actresses. But with a pandemic, putting on a show for theatre is almost impossible because it takes a large group of people to create and run the show, and an even larger one to make up the audience who watches it. Suddenly, we have a lot of people who had airtight schedules that were previously damn-near impossible to coordinate, blocked off by an entire season of performances for various schools and companies whose calendars are now entirely cleared up. Suddenly, everyone has the time to rehearse, as well as a hunger to work on anything at all.”

The team has also found a way to maintain a sense of normalcy for the production, even though it’s entirely remote. “Google Meet has come in absolutely clutch this whole time,” Jacobson said. “We use it almost every day. Every feature is essential. Screen sharing? Check. That one extension that lets you look at everyone in the call in a grid view? Check. We use all of it.”

While the crew is definitely using every tool and trick that they’ve learned growing up in the 21st century, Jacobson said they still face a major problem. “We don’t know when we’re actually gonna be able to shoot this.”

They’d like to shoot in the last week of June, but plans, of course, are tentative at best. “Our backup plan, which looks like more and more of a reality every day, is to shoot across two weekends in the beginning of August,” Jacobson said. “But even that’s in the air as a possibility for now. So we’re just doing as much planning and moving it along as much as we can with what we are able to do.

“We are trying to do this with a full crew, because we want it to look and feel as professional as we can, for both the audience and for the people working on it, but that obviously takes a lot of people in one place at the same time, and it’s impossible for us to do something like that with what’s happening in the world right now. So we’ll see,” she said.

Five Minutes is currently scheduled to be released in November of this year, just in time to do the rounds at the local film festivals set for spring of 2021.

In the end, there is no definitive answer for the fate of television and film as the industry and its constituents do their best to adapt to and take advantage of the situation that the COVID-19 pandemic has created.

At the highest level, this is a radical shift for the tried and true model that’s been established in the industry for over a century and that trickles down to many of the people who operate in that sector of the industry. “Maybe 95% of all the people in TV production and film production who’re working for production companies are contract employees,” McOsker said.

“As soon as this thing hit, with the stay at home order across the country, basically all of the production companies pulled the plug on all of the productions, and people went from having a full calendar to zero work. It was a huge rug that just got pulled out from underneath everybody’s feet and now everybody’s trying to adjust and adapt really quickly to try to stay busy and then also bring in money,” he said.

However, none of this is stopping people like Garland or McOsker from doing everything in their power to prevent that from becoming a reality, nor is it preventing the up-and-comers like the team behind Five Minutes from trying to break into the industry themselves.

After all, these are the people whose names fill the seemingly endless list of credits at the end of every film and TV show that many people don’t sit through. These are the people who put hours of their lives handcrafting the advertisements that many people scroll past or skip without thinking twice.

These are the heroes behind the screen.