Thursday, November 21st, marked the date for one of the most important events in the history of American Politics. Although it may not seem like it, the rules for filibusters have just undergone a complete change, completely rewriting the way that Washington operates. Even a few years ago a few thought this game changer would actually happen, but now many think of this as a long overdue necessity.

There are two parts to the filibuster process: The actual filibuster, and the vote to end it. The filibuster, when originally created, allowed a minority passionate about an issue to hold the Senate floor in order to ensure that their voice was heard and understood before the Senate voted on that issue. The vote to end it, called a cloture, allowed the majority to end the filibuster if they had 60 or more votes. For a while this actually worked well, serving as an important part of the checks-and-balances system that has allowed our country to be successful. Now, the filibuster has become a dirty word synonymous with obstructionism and gridlock.

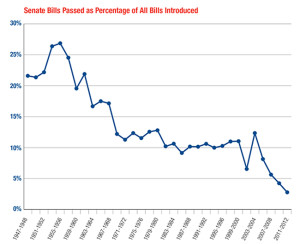

The problem is many say it is too easy for senators to conduct a filibuster. Before, this process actually used to be difficult, because the process to delay a bill or nominee involved standing on the Senate floor and talking for hours straight, without a break. An example of this was shown in the famous fictional filibuster Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, where Jefferson Smith talks for 24 hours straight to stop a corrupt bill from being voted on. This kind of thing was rare, because standing on the Senate floor and talking non-stop for such a long period time was extremely difficult. Now, if a senator has 40 votes (still a minority) of votes on his side, the mere threat of a filibuster is enough to block legislation (and has many, many times). No non-stop talking or debating is needed, and as a result, less bills are passed.

This has given the minority tremendous power to obstruct in the Senate. If they don’t want a bill passed or a nominee confirmed, it’s almost guaranteed to fail. Not-too-surprisingly this has caused lots of gridlock. During Obama’s presidency alone, barely into its second term, there have been 82 filibusters of his presidential nominees. Over the course of the entire history of the United States before Obama, well over 200 years, there have been 86 filibusters of nominees. To put it in other words, before Obama’s presidency, a presidential nominee was filibustered on average roughly once every 3 years, during the Obama presidency, that rate is almost 50 times higher than before.

This unprecedented obstruction has led to a change so ground-shaking, it has been dubbed ‘The Nuclear Option’, because this completely changes how the Senate functions. Not only that but it gives the president and the majority party far more power than they had before. Now, Obama can hand-pick nominees and have the majority party in the Senate, the Democrats can in turn, confirm them without worrying about about being held up by a filibuster. In the short-term, this deals a major blow to the head of gridlock in the Senate, but the effects are much more widespread, and will be seen for years to come. This change inflames party tensions all across Washington, and since the Nuclear Option doesn’t apply to the filibusters for legislation, or Supreme Court nominees, we will likely see even more gridlock in those areas. Even more monumental, this will allow future presidents and parties to do the same thing, suppressing the voice of the minority party.

This unprecedented obstruction has led to a change so ground-shaking, it has been dubbed ‘The Nuclear Option’, because this completely changes how the Senate functions. Not only that but it gives the president and the majority party far more power than they had before. Now, Obama can hand-pick nominees and have the majority party in the Senate, the Democrats can in turn, confirm them without worrying about about being held up by a filibuster. In the short-term, this deals a major blow to the head of gridlock in the Senate, but the effects are much more widespread, and will be seen for years to come. This change inflames party tensions all across Washington, and since the Nuclear Option doesn’t apply to the filibusters for legislation, or Supreme Court nominees, we will likely see even more gridlock in those areas. Even more monumental, this will allow future presidents and parties to do the same thing, suppressing the voice of the minority party.

Many speculate this will open the floodgates for further stripping of filibuster rules in the future. If filibusters for bills are stripped, for example, this could to the repeal of Obamacare. For example, if Republicans take the Senate and keep the house (which is incredibly likely) in 2014, they would have the votes to overturn Obamacare, and without a filibuster by the Democrats only a veto could stop them (with enough votes even that can be overturned). While those filibuster rules are still likely to stay put, these recent changes do increase the chances of even more sweeping elimination of the filibuster

Fundamentally, Democracy is about having every voice be heard, no matter how small, but

Democrats claim this change, in an age of never-before-seen obstruction, had to be enacted. The effects of this are big, but many worry about an even bigger picture: the state of Washington. If so little is getting done that over half of a major legislative body worry has to completely change the rules of an institution for even a little progress, what does that say about the state of American politics?