The Minority Myth

Students look to reshape perceptions of minorities

Olivia Harston ‘22 enjoys watching a movie. They helped AASIA get back on it’s feet and connect students at Monarch.

The swift movement of short, dark hair glides through the hallway past a sea of faces. Olivia Harston ‘22 is part of the crowded halls at Monarch High School.

Yet in a high school that is predominately white, Harston, a half Japanese-American student who uses they/them pronouns, often struggles to find students they relate to. “You realize most people around you don’t look like you and don’t have the same cultural background as you,” Harston said.

According to the website Public School Review, Monarch High School is 78% white, which brings plenty of struggles to Harston, an Asian-American student.

“Since I’m one of the few Asian kids in my classes, if we’re talking about a certain subject, teachers look at me and want me to talk about something just because I’m Asian,” they said.

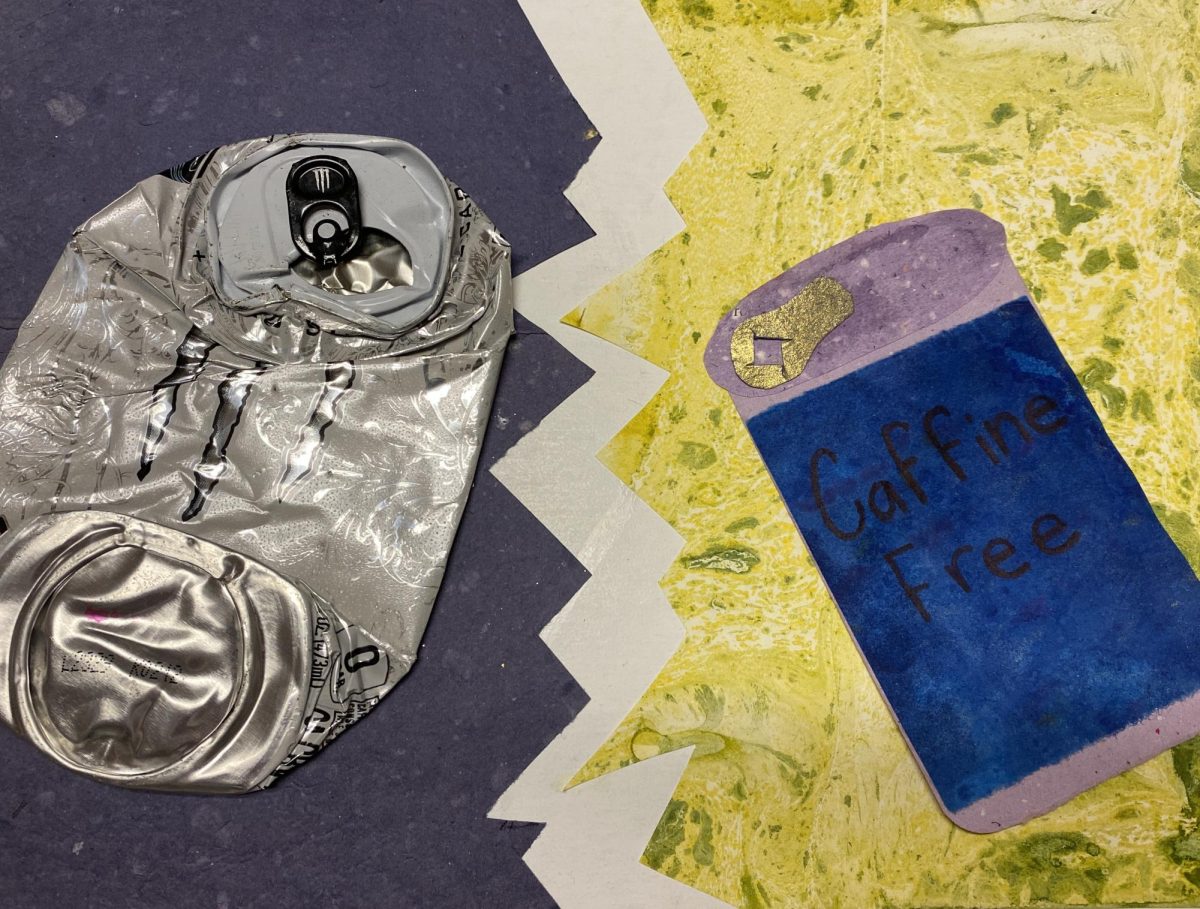

This can be attributed to the Model Minority Myth, the flawed idea that all Asians are smart and get straight A’s.

According to Learning for Justice, when Asian-American students don’t reach the high standards that peers and teachers hold them to, they can be singled out and essentially ridiculed for their so-called failure.

“The stereotype that ‘all Asians are smart’ can be pretty harmful to the Asian community and mental health,” Harston said. “It’s part of the reason why I have a hard time with school and grades.”

This expectation can be extremely harmful to the mental health of Asian-American students, according to Learning for Justice.

Those who do get high grades feel as though they can’t get anything lower. And those who get lower grades, feel as if they are less than. As if they are failures.

“A lot of my self-worth is dedicated to school,” Harston said. “I put so much blame on myself when I don’t get a good grade.”

This problem can get worse when facing more blatant forms of racism. While Harston appreciates their ethnicity and heritage, they sometimes feel like some white students and teachers aren’t accepting of others’ cultures and make uncomfortable comments, often without any awareness of the effect of their words.

“I spoke with a teacher who said some offensive things, and luckily they were very understanding and apologized for it, but the kids not so much,” Harston said.

Harston leads Monarch’s Asian-American Student International Association (AASIA), which aims to make it easier for Asian-American students to build connections with other students.

“The Asian community at the school is pretty small,” Harston said. “I just wanted to meet more people.” With only 5% of the school’s population being Asian, encountering other Asian-American students is rare.

Finding other Asian-American students is not the only thing that Harston has a hard time with. Because they have a mixed ethnicity, Harston undergoes a sort of internal identity struggle as well.

“I think a lot of people think being mixed is bad because of the identity struggle that comes with it,” Harston said. “I definitely have experienced that, but I feel like it has helped me figure out more of who I am.”

Harston isn’t the only student of color at Monarch who has felt singled out and stereotyped because of their ethnicity.

Remelia Hubbard ‘23 is an African-American student who goes through comparable struggles.

“It can be hard not to see a lot of people like you around, exhausting even,” Hubbard said.

African American students represent 1% of the student population at Monarch. Although she doesn’t often face extremely obvious or blatant racism, she said microaggressions are a dime a dozen.

“The whole ‘angry black woman’ thing. I get that a lot,” Hubbard said. “People usually think that I’m trying to argue with them.”

The “angry black woman” stereotype, similar to the Model Minority Myth, can negatively affect the mental health of African-American women, according to Forbes.

Many African-American women tend to suppress feelings of anger or even distress because they fear fitting into this inaccurate stereotype. Holding back feelings to not be perceived as an “angry black woman” can cause mountains of stress, according to Forbes.

Despite Hubbard’s actual personality, she feels people have predisposed ideas in their minds about her before they even talk to her. In her opinion, they characterize her as angry because she’s black.

“I like to voice my opinion to other people,” Hubbard said. “I think sometimes they think that I’m trying to start an argument, but I’m not.”

Not only do people characterize Hubbard based on her outgoing personality, but she also feels they invade her personal space without asking.

“People try to touch my hair without my permission a lot,” she said. “It makes me really uncomfortable. They also compliment my hair a lot more than other people’s hair just because it’s different.”

Students aren’t the only people guilty of doing and saying insensitive things.

“I’ve had teachers that assume that I would do worse than other students,” Hubbard said. “It really upsets me because they don’t think I’m capable of good grades even though I’m usually a straight-A student.”

Assumptions like these are harmful to students like Hubbard.

Not only do the stereotypes negatively affect mental health and self-image, but they also negatively affect students who may or may not fit into the stereotypes, similar to Asian-American students and the Model Minority Myth.

Hubbard is a media and outreach director for Monarch’s Black Student Union (BSU). The club’s main goal is to create a safe place where African-American students can feel comfortable.

BSU is not only for black students, but also for students of other races and ethnicities to show that they are allies to African-American students in the school.

Educating people about cultural and racial diversity is important. BSU adviser, Tony Tolbert, said BSU’s goal is to do just that and more.

“We have to educate enough of the staff and the students so they know that it’s civil rights and inclusivity that we’re talking about,” Tolbert said.

Tolbert, Hubbard, and the rest of BSU strive to make change in the school and its curriculum to be more inclusive of all students and teachers, regardless of race, gender, or religion.

“Every person in the building can be involved in this and involved in this change,” Tolbert said. “If every person got involved in the changes, then the little things we’re asking for would get accomplished.”

Last school year, BSU approached the school faculty with a few ideas and proposals in order to make this change.

“We talked to the teachers about the school curriculum to help it be more inclusive of all people,” Hubbard said.

Tolbert said the organization’s attempts to create change and inclusivity in the school have been impactful so far.

Even with their successes, BSU struggles on a daily basis. They lack the numbers in members and the time to create the change that they want to make.

“The enthusiasm is there, but it feels like there’s no time, like we haven’t been able to breathe,” Tolbert said. “We’re still doing it, though. We’re still trying to make it happen, and we’re still looking for more and more people.”

Fortunately, the school has fully supported BSU and its goals. The support the school has given them has pushed them to continue this process of change.

“The school was very open and willing, and I thought the administration was very open and willing,” Tolbert said.

By creating an inclusive culture, BSU hopes to make the school environment feel even more comfortable for minority students like Harston and Hubbard.

“The white students here don’t seem to be affected by students of color,” Harston said. “Race isn’t a big deal to them.”